Tiny surgical robots are learning to make decisions inside the human body, using AI to interpret complex biological environments in real time. Unlike traditional minimally invasive procedures, where precision occurs at the tip of a rigid instrument, these microrobots navigate through tissue, gather data, take biopsies, and deliver treatment.

The challenge is not just building devices small enough to move through living systems. It is designing tools that operate in messy, unpredictable environments where fluid dynamics, anatomy, and biology constantly push back.

The “mom rule” for robots

Robeauté is steering microrobotics into the neurosurgery operating room. Co-founded by Joana Cartocci and Bertrand Duplat, the Paris-based startup is developing a microrobot of 1.8 millimeters in diameter that moves through brain tissue along curved, pre-planned 3D paths instead of the straight lines imposed by today’s rigid needles.

What convinced Cartocci that this could be more than a research experiment was Duplat’s personal motivation. This robotics pioneer had spent his career building robots for space, nuclear environments, and even the pyramids of Giza. Then he lost his mother to glioblastoma.

“Seeing what it was like not to have the right tools to intervene meaningfully in the brain… he wanted to do something about that,” Cartocci said.

Credit: Palta Studios, Robeauté

The robot uses the world’s smallest micro-motor, according to Robeauté. A thin tether provides power, enables tracking and allows retrieval. The surgeon directs each action, while AI supports trajectory planning and provides real-time guidance. Unlike passive magnetic microrobots that follow external magnetic fields, Robeauté's device can follow nonlinear trajectories and pull biopsy tools or catheters behind it.

Safety is non-negotiable. Cartocci calls it the “mom rule”: “If it is not safe enough for your mom, it is not safe enough for anybody.” Robeauté is now in live pre-clinical studies, with first-in-human procedures planned for 2026.

Building the bridge from lab to clinic

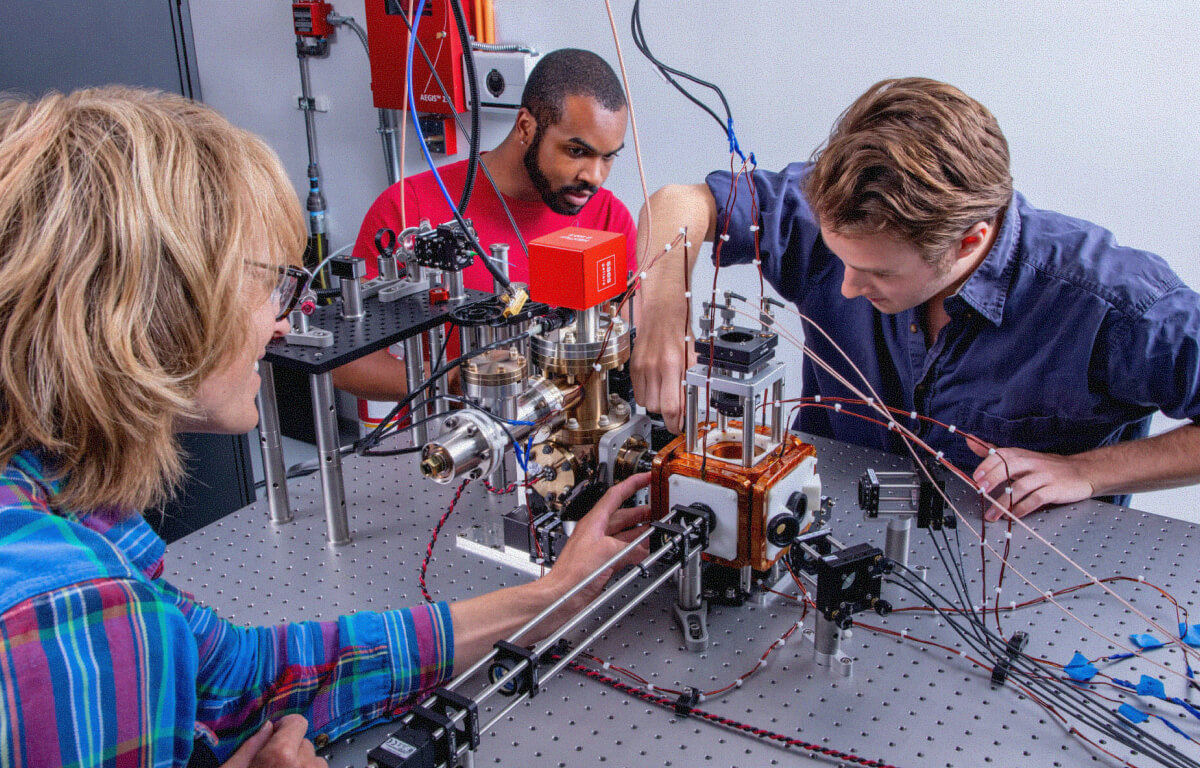

Professor Bradley Nelson has spent more than 20 years developing machines that can move within the body. At ETH Zurich, his team focuses on one of the field's hardest problems: making microrobots visible and controllable as they navigate living tissue.

His group has built a steerable capsule less than one millimeter in diameter that is guided by external magnetic fields. Iron oxide enables control, while tantalum makes it visible under fluoroscopy so surgeons can track its movement.

“Visibility was one of the hardest problems,” Nelson said. “Any device used in real patients needs to be reliably imaged as it moves.”

The capsule can carry a drug payload and release it at precise locations. Nelson said this could help treat hard-to-reach tumors by concentrating the dose at the disease site while reducing systemic toxicity.

Control, navigation and imaging remain the core challenges. The team has spent years shaping magnetic fields to penetrate tissue safely — work that has improved existing surgical tools as well. Adding a small magnetic element to the tip of a guidewire, for example, lets surgeons steer it with greater precision. Nelson’s spinout, NanoFlex Robotics, has already demonstrated this capability by performing a remote thrombectomy with the surgeon in Zurich and the patient in Phoenix, Arizona.

He expects magnetically directed guidewires to reach patients by 2026, creating a regulatory bridge for future microrobots. Nelson said advances in imaging and control will eventually open the door to AI-assisted automation in certain procedures, although he expects clinicians to remain in control for delicate tasks.

Endiatx: Cutting the cost of endoscopy

Endiatx, based in Hayward, California, is developing PillBot, an ingestible robot that enables clinicians to control a gastric exam in real time without the cost and complexity of traditional endoscopy. Standard diagnostic procedures can cost thousands, involve several clinical staff and require multiple visits. PillBot offers live video through a capsule that the patient swallows and must be “affordable enough to flush down the toilet,” according to Endiatx.

The device uses pump-jet motors to maneuver within the stomach. A clinician views and steers it through a software interface. The goal, CEO Arman Nadershahi said, is to combine the comfort of capsule technology with real-time, operator-directed control to create a new class of robotic visualization tools.

According to Endiatx, the development roadmap centers on AI and closed-loop control systems. The company is testing how machine learning algorithms can enhance image quality and stabilize the visual field as the capsule moves through the stomach.

“Over time, AI could take on a greater role, enabling autonomous functions under physician supervision,” said Nadershahi.

PillBot remains under development. A regulatory submission is planned for 2028.

Fighting the fluid dynamics using AI

Professor MinJun Kim at Southern Methodist University in Dallas studies how microrobots move inside complex tissue. His group designs bacteria-inspired swimmers, modular magnetic robots and soft devices for drug delivery and diagnostics. The goal, he said, is to build machines that behave reliably in the body rather than only in controlled experiments.

“A lot of our work focuses on understanding how these robots behave in low Reynolds number environments,” he said. “At this scale, the physics are completely counterintuitive.” Put simply, in this micro-world of human tissue, fluids are incredibly sticky. The moment the robot stops pushing, it stops moving. It's like trying to swim through honey instead of water.

Kim sees unpredictable fluid mechanics as a significant obstacle.

“Biological fluids are viscoelastic and heterogeneous,” he said. “Inside the body, viscosity changes from one region to another, and that makes precise motion very challenging.”

Visibility is another constraint. Optical tracking often fails within the eye or brain, so his team is developing magnetic localization enhanced with AI.

“We integrate an artificial neural network with a Kalman filter so we can track microrobots even under very low signal conditions,” he said. A Kalman filter is a statistical estimator that helps the system determine the robot's position when sensor readings are weak or noisy.

Kim expects the first clinical applications to be intraocular therapies because the eye offers a confined, predictable environment. Neurovascular and cardiac uses could follow as control systems mature.

Progress now depends on solving problems that traditional robotics rarely encounters, including viscoelastic fluids, sub-millimeter localization, and safe imaging inside living tissue.

If these teams succeed, surgeons could gain instruments that reach areas today’s tools cannot. Biopsies could follow curved paths, drug delivery could become more targeted, and procedures could be guided by data gathered directly from within tissue.

The first approvals may arrive within the next two years. What follows will show whether microrobots can take their place alongside the most precise tools in modern medicine.

Lead photo credit: Endiatx